Many craft beer styles are pretty neatly defined in the minds of beer drinkers. We more or less know what we’re getting when we order a hefeweizen or an imperial stout, or even—as long as the brewery conveys the substyle—an IPA. Variations exist, but the basic profile of these styles stays pretty consistent. American Brown Ale, however, is more of a moving target.

[newsletter_signup_box]

The Brewers Association’s 2018 style guidelines describe the style as having low to medium hop aroma, medium to medium-high bitterness, and moderate levels of caramel, chocolate, and roasted malt character. While those provide some boundaries, they leave much to the imagination of the brewer creating a new example of the style, and brewers do indeed interpret American Brown Ale in wide a variety of ways.

Homebrewing Roots

As with many modern craft beer styles, we have homebrewers to thank for American Brown Ale. Scott Birdwell, the owner of DeFalco’s Home Wine and Spirits Supplies in Houston and a pioneer in the early homebrewing movement, fondly remembers the early brews that laid the foundation for the beer style. The first whisperings of the new style came to him from some California homebrew shop owners at a conference in the early 1980s.

“They were telling me about some brown ale recipes that were kicking butt and taking names out there in California, but getting hosed at the national homebrew competitions,” recalls Birdwell. At the time, the understanding of brown ale was taken from the classic English versions, which were much milder beers than these new homebrewed versions. “These were really nice beers, but, frankly, didn’t fit the style guidelines in use at the time. These new brown ales were too assertive. The bit of roastiness was forgivable, but the hop bite and bouquet were a deal-breaker for the brown ale category.”

(Relate: A ‘Stirring Tale’ Behind the Father of Homebrewing’s Famous SpoonOpens in new window)

Birdwell began adding a “California Dark Ale” category in homebrewing competitions back in Texas, and before long amateur brewers nationally were crafting beers known as “Texas Brown Ale.” Soon, commercial beers like Pete’s Wicked Ale and Big Sky Brewing Moose Drool brought a slightly toned-down version to store shelves. Birdwell says that at point the Texas Brown Ale became the American Brown Ale.

But what is modern American Brown Ale? The answer can be tricky to nail down.

So What’s a Brown Ale?

“Brown ale has always been a little nebulous,” says author and beer historian Randy Mosher. “I think ABAs reflect that American penchant for disregarding conventions and forging ahead with bold, inventive interpretations.”

Historically, brown ale began as a loose collection of brown, top-fermented beer styles in England that eventually coalesced into the porter style in the 17th century. The style had become an afterthought in its own country by the time a few intrepid homebrewers rediscovered the style on the other side of the Atlantic two centuries later.

(Style Spotlight: American Brown AleOpens in new window)

I asked some professional brewers who have had success with the style to offer their expertise on what American Brown Ale is and isn’t.

Avenues for Experimentation

Yellow Springs Brewery in the eponymous small town near Dayton, Ohio, opened in April 2013, and current head brewer Jayson Hartings started as a production worker just months after the brewery launched. The brewery made Handsome Brown Ale one of their first beers.

(More: Wisconsin Brewers Bring Old, Rare and Unusual Beers Back to LifeOpens in new window)

“I worked very closely with the head brewer at the time, Jeffrey McElfresh. He preferred a more bitter charge for that beer,” recalls Hartings.

“We brew Handsome with American 2-row malt, and it’s pretty clean. There’s no real English biscuity character,” comments Hartings. “There’s a touch of Munich malt and some English pale chocolate malts. It has a little of the roasty chocolate and coffee notes in the balance but there’s none of that roasted barley character. There’s a good amount of Columbus hops in there. We’ve been accused of Handsome being more of a brown porter. It’s got some pretty bold flavor for a brown ale.”

So what’s the difference?

“It’s a real swim-line,” admits Hartings. “If we made a porter. It would not be that different.”

The use of American hops is one defining factor.

“Columbus has a real pungent depth to the hop,” says Hartings. “Handsome is a very American brown. It’s got the American hops, the boldness, the bite. It drives that style pretty much to the limit.”

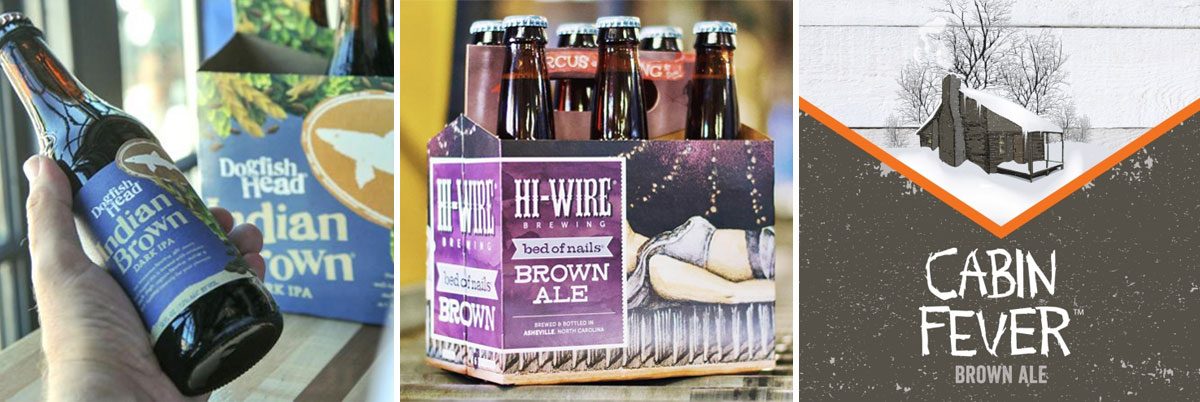

He mentions Dogfish Head Indian Brown Ale, which that brewery refers to as a “Dark IPA,” as an example of a beer further pushing the hoppy boundaries of American Brown Ale.

(Related: Dogfish Head Makes a Statement with New 60 Minute IPA PackagingOpens in new window)

“I love the English styles of brown ale,” he reflects. “But the avenues for experimentation [for American Brown] open things up a bit. It’s just the evolution of it, people are trying a lot of different things with it. That’s a good reason we’ve seen diversity within the style.”

Jason Salas, brewery operations manager at New Holland BrewingOpens in new window in Holland, Michigan, thinks that need to experiment is driving the divergence from classic flavor profiles. His brewery’s own brown ale, Cabin Fever, is a seasonal release that doesn’t hew too closely to the style guidelines.

“I think it’s maybe approaching the boundaries of what a brown ale technically is,” says Salas. “We wouldn’t be sending this into a brown ale competition. It’s more roasty, like a stout.”

At Hi-Wire BrewingOpens in new window in Asheville, North Carolina, head brewer Luke Holgate has taken a more classic approach to American brown ales with his Bed of Nails Brown Ale.

“I really wanted to do a nod to the traditional brown ale,” he says. “Keep the roast character out of it and not make it a light porter.”

Holgate builds malt complexity with Special B malt from Castle Malts, which produces dark fruit, cherry, and plum notes, as well as with an astonishing amount of crystal malt.

(More: A Brief History of Hip-Hop Craft BeersOpens in new window)

“Any traditional brewer would look at me like I’m crazy for the percentage of crystal malts we use in Bed of Nails. About 30 percent of the grist is varying degrees of crystal.”

“I think brown ale is underserved, but I feel like there’s a lot more diversity now,” reflects Holgate. “I really feel like 5-6 years ago it was just a light porter that was aggressively hopped. You can brew a more English brown ale now.”

Holgate sees this variance within the style as indicative of the broader market.

“It’s just kind of the reality now. IPA was so popular it made sense to split it up into different categories.”

Will the Real American Brown Ale Please Stand Up?

So which of these is a real American Brown Ale?

All of them.

The style sits at the intersection of easily definable flavor bookends. It can have moderate hop bitterness and flavor, but not as much as IPA. It can have moderately rich maltiness, but not as much as bock beer. It can have moderate roastiness, but not as much as stout. If you draw a circle around American Brown Ale, it’s easier to label the borders than it is to label the center.

American Brown Ale’s flavor profile doesn’t immediately seem precarious or transitive, but if you significantly elevate or diminish any of its major flavor descriptors, you tilt its entire flavor profile in a new direction. If you make an IPA more or less bitter or hoppy, you get a more or less bitter and hoppy IPA. If you adjust the roast on a stout, you get a more or less intensely roasty stout. Shift these attributes on American Brown Ale, and you slide into a different style altogether.

Scott Birdwell, who was there at the style’s inception, sees sharper distinctions between the style’s origin and its present interpretations.

“These days, we still refer to Texas Brown Ales,” he says. “They’re extreme American Brown Ales: O.G. at least 1.060 and 40 IBUs. But that may just be me.”

His final words highlight the central difficulty of defining this modern classic. American Brown Ale, more so than many styles, is exactly what each brewer thinks it is.

What does that mean for us as drinkers? Craft beer is all about exploration, but we often pigeonhole ourselves when we go to a taproom, not venturing from flavors we know we like. When you order a brown ale today, you have a loose idea of what it will taste like based on the style guidelines, but there is much room for the brewer to do something unexpected. It might sound counterintuitive to think of ordering a brown ale as an adventurous choice, but the style offers more room for surprises than you might think. Be brave, order a brown ale, and see how the brewer has interpreted this fascinating style.

CraftBeer.com is fully dedicated to small and independent U.S. breweries. We are published by the Brewers Association, the not-for-profit trade group dedicated to promoting and protecting America’s small and independent craft brewers. Stories and opinions shared on CraftBeer.com do not imply endorsement by or positions taken by the Brewers Association or its members.

Share Post