Without farms, we don’t have beer. With so many breweries housed in industrial parks, it can be easy to forget that beer is an agricultural product at heart. But a movement among craft brewers in recent years is returning beer to the rural land where its ingredients are grown.

Some breweries are taking this link a step further with an unexpected agricultural addition: farm animals. Breweries are raising cows, goats, pigs and other livestock in order to revive the land, reduce waste and educate the public about the ecosystem that pairing livestock and lagers can create.

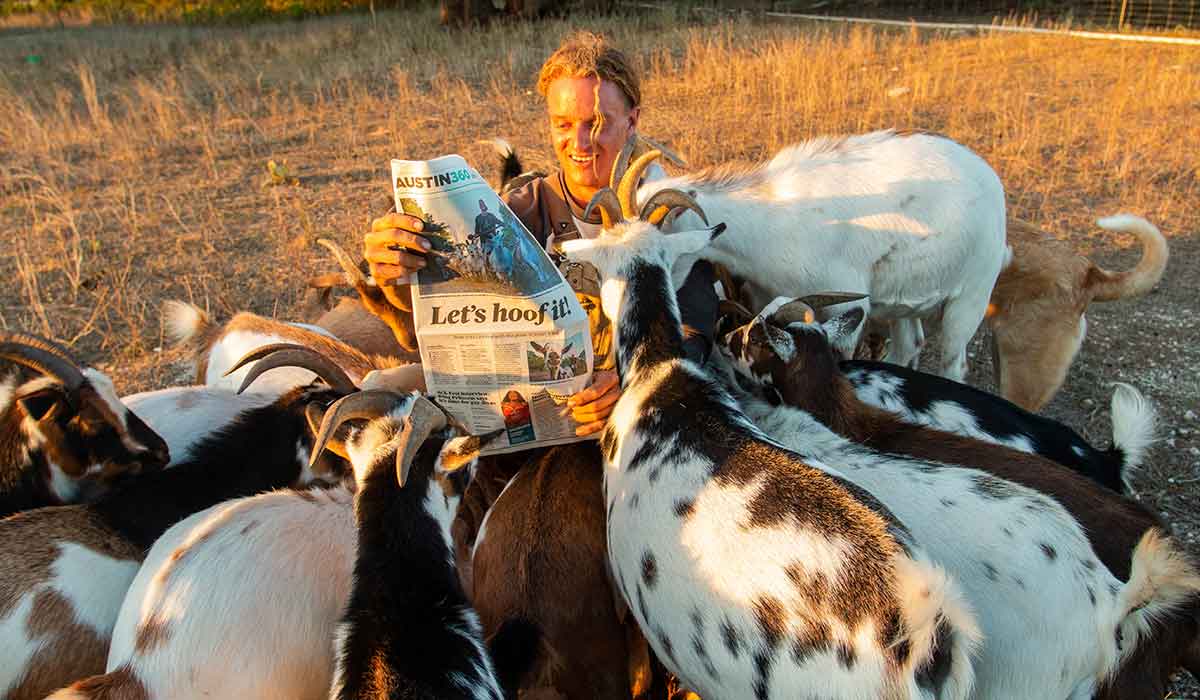

Jester King Brewery’s ‘Prince of Goats’

“Hi, I’m Peppy. People call me Farmer Peppy. Or just, you know, Prince of Goats.”

That’s Sean “Peppy” Meyer, the resident farmer and goat herder at Jester King BreweryOpens in new window outside Austin, Texas. When he was hired in 2018, his only stipulation was that he be allowed to bring his goats with him. Brewery founder Jeff Stuffings agreed.

“We all moved into the goat barn together for a year,” says Peppy, who lived with his 20 goats until this last summer. “I’ve since moved off the farm and have been reacclimating to humans. I’ll be moving back into a small trailer on the farm soon, because it’s kidding season. We’re expecting about 25 babies.”

Peppy thinks American farms lost something when animal husbandry became industrialized.

“If you want to have a sustainable program, then it’s a necessity to have animals. We replaced animals with machines, and it’s just been empty ever since,” he says. “It makes the job a lot easier when there’s mutual understanding and respect. The animals receive a better life, and we receive the products they yield, such as fertilizer and milk.”

(READ: Established Craft Breweries Plant Rural Roots)

Fresh Milk and Beer Sold Here

Speaking of milk, Stone Cow BreweryOpens in new window near Barre, Massachusetts, is operating a brewery on a working dairy farm that’s been owned by the same family for more than 80 years.

Molly DuBois’s grandfather bought the farm in 1938, and his descendants have been milking cows here ever since. Molly and husband Sean, along with her brother Will Stevens and his wife, Shayna, manage a herd of 200 dairy cows and operate a brewpub. There aren’t too many breweries where you can walk out with both a six-pack of beer and a pint of fresh, raw milk.

“There’s not a lot of money in wholesale milk,” says Molly. “We can get maybe .13 to .15 cents for a pint of milk at wholesale, but in the taproom we can get $5-$8 for a pint of beer. The brewery has saved not only our farm, but our way of life. We didn’t want to be the generation to stop milking cows here.”

Her husband agrees.

“Molly’s grandpa bought this farm from a family who had been farming here since 1749,” says Sean. “We have 1,000 acres that have been farmed by two families in 260 years. We inherited something we feel is pretty special.”

Pigs and Pils

Wooly Pig Farm BreweryOpens in new window in eastern Ohio sits on 90 acres of mixed pasture and woodland draped over a few small hills. The owners raise a rare Old World breed of pig on the property.

Founder Kevin Ely has taken frequent trips to Franconia in Germany during his brewing career. He first saw Mangalitsa pigs on a bicycle tour through the region years ago.

His sister-in-law, Lauren Malenke, is a large animal veterinarian. She was able to identify the shaggy Eastern European breed from his photos. Lauren and husband Aaron, along with Kevin and his wife, Jael, all noted the similarities in terrain between Franconia and eastern Ohio, and Kevin recalled how many rural and small-town breweries in Germany had raised pigs to help get rid of spent grain. They decided their new brewery should carry on the tradition.

Wooly Pig raises about 30 pigs, and Aaron is responsible for their care.

“We also have about 30 sheep, a couple horses and a llama,” he says “Oh, and a goat named Hoppy Phils.”

(VISIT: 2020 Great American Beer Bars)

Brewery Livestock Reduce Waste

At Wooly Pig, every bit of waste from the brewing process goes to feed the Mangalitsas.

“They do really well with basically all organic waste streams generated from the brewery,” says Ely. “Some other animals can be more finicky, but pigs are more robust and flexible. Seeing those old breweries in Franconia, as the spent grain was being shoveled out, it would be shoveled right into the hog barn.”

“Other farmers sourcing grain from breweries, they have to pick up several days at a time, and have vehicles and containers for it,” says Aaron Malenke. “I basically have it at my disposal.”

“We’ve built our brewery around being able to feed our pigs all of our spent grain, all of our weak wort, all of our spent trub and yeast, our spent beer,” Ely says. “This makes it viable for us to be doing what we’re doing on this farm without a wastewater treatment plant supporting us. And we’re eliminating the impact of vehicles and fuel.”

Wooly Pig is tailoring the size of its animal herds to the amount of waste the brewery is producing. If the brewery grows, they’ll expand their livestock program to match it.

While cows can’t tolerate quite as much spent grain as pigs can, Stone Cow is dividing its grain among the herd of 200, which is otherwise grass-fed.

“Spent grains are amazing to put in a cow’s diet,” says Sean DuBois. “They produce more and better-tasting milk. You’ve extracted the majority of the sugar, and you’re leaving them with all the good stuff.”

At Jester King, spent grain goes to a local Wagyu beef farm, but Peppy has another plan for how animals can reduce the environmental impact of trucking.

“We’re getting mules. It’s going to be so badass,” he says. “They’ll help with transportation by hauling stone and other stuff. Hauling kegs. Unlike vehicles, they won’t compress the soil.”

Breweries Raise Livestock, Revitalize Land

Peppy is just as passionate about the role of livestock in reviving mismanaged farmland and prairie.

“The majority of America was once a prairie developed by bison, and we essentially exterminated them,” he says. “It’s up to us to move these domestic animals through now.”

Prairie grasses grow up into the sun but also down into the soil, he says. When animals eat the foliage above ground, it stimulates the grasses to expand their root structure, which provides a setting for a rich ecosystem of microorganisms in the soil and prevents erosion. The plants and the soil sequester carbon.

“Take away the animals and the roots die, and all that carbon blows off in the wind,” he says. “If you take away that mammalian presence, it just falls apart.”

By carefully managing the grazing pastures for his goats and, soon, sheep, Peppy can help redevelop land that was damaged by industrial agriculture for decades.

There’s another obvious agricultural benefit to pairing livestock and brewing: free fertilizer.

“Every week I harvest three wheelbarrows of manure from the goat barn,” says Peppy. “That’s gone into our planting beds.”

While feeding spent grain to livestock removes carbon emissions from waste management and transportation, the benefit goes in the other direction as well at Stone Cow. The barbecue restaurant attached to their taproom serves grass-fed beef and vegetables grown right on the property.

“You’ve heard of farm-to-table,” Sean says. “We like to say we brought the table to the farm.”

Additionally, Stone Cow’s food is cooked over wood responsibly harvested from their land.

“It’s a pleasure for me to be able to go out before the sunrise and pick some cauliflower and then that evening see people drinking our beer and eating fire-grilled vegetables,” Molly DuBois says. Stone Cow hopes to begin making cheese with their milk soon as well.

Ambassadors for Responsible Farming

All three breweries see their four-legged charges as a way to educate beer lovers about responsible farming practices.

Peppy corrals the curious among Jester King’s couple thousand visitors each weekend to teach them about the regenerative agriculture of the animals.

“I’ll stand on a table and yell the farm tour call,” he says. “‘You want to come learn about farms? Also, there’s really cute goats.’ And that’s when everyone stands up and is like, ‘Hell yeah, I want to drink a beer and pet a goat.’ Then I’ve got 50-100 people for an hour. I try to explain as much as possible about agriculture and how we got separated from the land.”

While much of this education is purely informative, Peppy also lets folks touch and interact with the goats.

“It’s fun to watch the larger goats interact with children in such a delicate manner,” he says. “They sense it’s this little human, and they have to be gentle.”

The Wooly Pig team uses its livestock to help educate the public as well.

“The pigs really do make this place family-friendly,” Malenke says, echoing thoughts shared by the Stone Cow crew. “People want to see the new piglets. They want to feed squash to the llama. That all helps. Most people haven’t been on a real working farm. It’s not just a petting zoo.”

The brewery also hosts a kids’ weekend every summer with additional animals from neighboring farms. It all helps drive home how natural it is for farming and brewing to be linked (and for families to be present for both). Even other farmers can learn from this.

“We have farmers who come into the brewery all the time who are raising pigs, and they’ve never seen a Mangalitsa, and they’re not used to seeing pigs on pasture,” says Ely.

(TRAVEL: Visiting Fairbanks, Alaska, for Craft Beer)

Brewery-Raised Livestock ‘Living Their Best Lives’

At Wooly Pig, Kevin Ely is as passionate about raising animals in a responsible way as he is about brewing authentic German lagers.

“We’re raising these animals in as respectful a way as possible,” he says. “Lots of space, ample feed and clean water, shelter. They’re living their best lives. It’s an integral part of how we manage to operate our brewery and farm in a remote space.”

“Lots of space, ample feed and clean water, shelter. They’re living their best lives.” Kevin Ely, Wooly Pig Farm Brewery

“We need to find a way that these animals are treated with honor,” says Peppy. “Historically, this was known to be a sacred being.”

The brewery’s founder is onboard with Peppy.

“We want to develop an ecosystem that can be a model for the state, the country, even internationally,” Stuffings says.

“We work hard as hell, but it’s special,” Peppy says with a laugh, before adding a thought that could apply to all three trailblazing breweries: “This place is a massive rebellion against the mundane.”

CraftBeer.com is fully dedicated to small and independent U.S. breweries. We are published by the Brewers Association, the not-for-profit trade group dedicated to promoting and protecting America’s small and independent craft brewers. Stories and opinions shared on CraftBeer.com do not imply endorsement by or positions taken by the Brewers Association or its members.

Share Post