Built by blue-collar workers and industry, cities associated with the Rust Belt have become great beer destinations. Recovery from the industrial decline in these areas is supported by creative culinary and beverage operations. From Pittsburgh to Cleveland and Detroit on to Milwaukee, cities are shedding their underdog reputations and ushering in a new era of pint-half-full optimism.

Meet some of the urban visionaries behind the renaissance through craft beer. Their stories feature bootstrappers refusing to leave their hollowed out neighborhoods during economic exoduses and prodigal sons and daughters who did leave home only to be drawn back by a sense of familial loyalty. Then there are the tales of urban frontiersmen and frontierswomen attracted by the promise of new beginnings in unlikely places.

Attracting People and Businesses to Reverse Pittsburgh’s Decline

Technically, Grist House BreweryOpens in new window is not in Pittsburgh–it is located in the town of Millvale across the Allegheny River, but the town suffered through the same troubles of the industrial decline that hit Pittsburgh.

“This town was hit with a one-two punch because after the steel mills closed down and people started leaving, there was a huge flood in 2004 that devastated this whole area,” says Eaton. “It cleared out a lot of the little businesses barely surviving and scared people away.” Eaton sees his brewery’s role in the community is to be a beacon for revival.

“Breweries can really change the face of a town like this and attract people and businesses who wouldn’t normally come here,” says Eaton. “We’re helping other businesses thrive. We’ve seen flower shops, tea shops and restaurants open up because together we are more visible and can attract more people.”

The biggest problem when first opening the brewery almost a decade ago had nothing to do with blight.

“Educating consumers about craft beer and what kind of business we were was actually the hardest part,” says Eaton. “We had people coming in for shots and Miller High Life and asking us what kind of bar we were if we didn’t serve those things.”

(READ: How Long is My Crowler Good?)

East End Brewing: Keg Marks the Spot

Scott Smith, founder of East End BrewingOpens in new window, did not care that the neighborhood where he was locating his one-man brewing operation 15 years ago was in a part of town many people in Pittsburgh did not find inviting.

“The Homewood neighborhood would primarily be known to many people in Pittsburgh as a call-out on the evening news about a crime or nefarious activity going on,” says Smith. “But none of that mattered to me because my original vision was just me in a warehouse making beer and delivering to bars and restaurants around town and Pittsburgh is a small city anyway and I had grown up not far from that area.”

When Smith discovered he could fill growlers, he began opening his doors to customers a few times a week, but his concern for becoming a target of property crime prevented him from putting up a permanent sign.

“We had a lot of nefarious activity on our block so I would just put up a hand-written sign that I would tape to the side of the door and we would put a keg out on the sidewalk,” says Smith. “Sometimes it would take people hours to find us; this was before everyone had GPS on their phones. Also, that keg was stolen twice and somehow magically came back to us.”

Serving beer to-go turned out to be a huge growth engine for the microbrewery and gradually things in the neighborhood began to change.

“Simply by putting new faces there, people coming to that street for a good reason, we saw a lot of that nefarious activity go away,” says Smith. “One of our customers was a beekeeper and he moved into a space across the street and then other businesses started coming in, too.”

Recently, Smith launched a campaign to create a beer named after each one of Pittsburgh’s 90 neighborhoods.

“Pittsburgh is our home and it feels weird to me that there are aspects of it that are completely foreign to me,” says Smith. “It’s a great opportunity for me personally and for our customers to explore and engage in parts of the city that are not as popular, or a little more forgotten, than other areas and connect with the people who live in those neighborhoods.

East End Brewing now has two pubs and taproom locations with actual signs, but putting a keg out to signify hours of operation is a tradition they still uphold.

The Cleveland Entrepreneur: Sam McNulty

Irony is not lost on Sam McNulty when people refer to his collection of small businesses as a small empire. For the last two decades, the entrepreneur has been busy building restaurants, brewpubsOpens in new window and bars in Ohio City, a deindustrialized neighborhood in his hometown of Cleveland, Ohio.

Born to a first-generation American father and a refugee mother, McNulty says the thing he is most grateful for in life is his hardships growing up.

“I think one of the worst forms of child abuse is to give your kids everything they could possibly want,” reflects McNulty.

As one of seven siblings, McNulty began his entrepreneurial path early out of economic necessity. As a child he became the family barber (he still cuts his own hair) and started delivering newspapers at the age of 11; a job he held until turning 21.

“My parents were both social workers, which isn’t exactly the best-paid job in the world, so I pitched in and learned a lot about business in the process,” he says.

McNulty credits his parents for his work ethic.

“My parents came here and even though to other Americans it might have looked like an undesirable place, to my parents it seemed like a paradise of opportunities,” says McNulty. “I think my parents’ story is the story of Cleveland’s revival because people like them moved here when others, the people who could have helped solve our problems by building new economies, were abandoning us in droves. Maybe that was a sort of weeding out process. Maybe we’re rebounding now because we were left with a good stock of people and good people moving in.”

Ohio City is also near and dear to McNulty’s heart for personal reasons outside of business. It is the neighborhood where his parents were swindled out of their first home after the house they were originally renting was demolished to make way for an overpass. A man in charge of negotiating the purchase of an Ohio City building for a group of families absconded with all their savings.

McNulty says those experiences taught him to always be on the lookout for the little guy and try to find ways to help them move forward.

(TRAVEL: Find U.S. Breweries)

Pretentious Barrel House Seeks to Provide Value to Columbus

As a transplant from California and the founder of Pretentious Barrel HouseOpens in new window, one of only a handful of Latino-owned breweries in Ohio, Joshua Martinez says he has gotten quite comfortable with not always fitting in.

“I don’t know why brewers are mostly white guys with beards,” Martinez says, laughing. “I’m not a white guy and I don’t have a beard, but one of my employees is a white guy with a beard and people always ask him how he founded the brewery.”

Although it has been more than a year since Martinez opened Pretentious Barrel House in a predominantly black neighborhood embedded in a former railroad hub, he says he struggles to define his business’s role in his community.

“We want to drive more commerce this way but not the gentrification type,” says Martinez. “How do we prevent that. How do we keep the neighborhood with its same personality?”

Part of Martinez’ strategy has been to find ways in which the brewery can serve the needs of the community.

“If you go to a fast-food restaurant here, there are people having meetings and although we might not yet be able to contribute money, we can contribute space for people from the neighborhood without asking anything in return,” says Martinez. “We are also going to host our first neighborhood cookout. We are working really hard to provide value here by reaching out in the most genuine way. The last thing we want to do is be patronizing or disingenuous with our intent.”

Although neighborhood pedestrian traffic to the brewery has increased as the weather gets warmer, Martinez admits most of his clientele is still coming from other parts of the city.

“There’s a motorcycle club across the street from us and it’s interesting because our customers are typically a lot more pale-faced than our neighbors,” chuckles Martinez. “When our customers show up and ask us if their car is safe here, we tell them, ‘Yes! Those guys across the street are riding $50,000 motorcycles, they don’t care about your Honda Civic.’ It’s actually an extremely safe area and we’ve never had any problems.”

As a “sours only” brewery, Martinez knows that regardless of location, his brewery was always destined to stand out, and he is okay with that.

Atwater Brewery Celebrates Detroit’s “Grit”

Mark Rieth, owner of Atwater BreweryOpens in new window, has staked his claim to brewing greatness on the belief that Detroiters are a special breed of people.

“We celebrate Detroit’s grit,” says Rieth. “Part of our logo is a blue-collar worker raising a pint of beer after a hard day’s work with a hard hat on and our main slogan is ‘Born in Detroit, raised everywhere’ because if you are from Detroit, no matter where you are, you’ll always have Detroit in your backbone.”

In its 22 years of operation, Atwater Brewery is now the fourth largest brewery in Michigan, but its path was not without challenges. Rieth, a Detroit native, returned to his hometown to invest in the brewery after stints in California, Massachusetts and Arizona working as an automotive industry professional.

“Detroit’s obviously been through a lot: prohibition, riots, bankruptcy and the automotive crisis,” says Rieth, “but the difference between people who invest here and those who don’t is that we can see past those downtrodden parts and look at the bones of it all and see that it’s solid.”

The automotive and manufacturing industry built a sophisticated infrastructure network of canals, rail lines and roads Rieth believes can be the foundation for a new and improved version of Detroit.

“Things are bad until they’re not,” says Rieth. “When we first opened there were tumbleweeds going down the street. Our population is now about 700,000 people and at our high point we had about 2 million. Things go up, things go down, but we have a good base for continued growth.”

On the topic of why craft beer has been a catalyst for so many of the positive changes, Rieth has a simple answer: “Beer is a vehicle for conversation and bringing communities together and that’s what Detroit needed and continues to need. We’ve learned from our mistakes and people who are here feel empowered by creating something together.”

(READ: Trendy Rosé Beers Reach New Drinkers)

Witnessing Detroit’s Revival Through the Lens of Beer

Steve Johnson very literally wrote the book on Detroit’s brewing scene: “Detroit Beer: A History of Brewing in the Motor CityOpens in new window.” Since 2009, Johnson has been leading bus and walking group tours to Detroit breweries and more recently he has added boats and bicycles to his offerings of tour vessels. Johnson also runs a monthly podcast featuring interviews with local brewers called Beer Tour Guy.

“I work with all the breweries in downtown Detroit and I know most of their stories,” says Johnson. “I work with the new guys and the ones that have been here for a while and I would say the more established breweries definitely have more of that revival theme to their stories because they were here when things were really bad.”

Johnson says some of the first breweries to begin popping up in the early 90s, as a result of state alcohol law changes, had to contend with prostitution and drug dealing happening right outside their doors.

“Now that’s gotten cleaned up but people still remember how bad the economy got and people getting laid off during the bailout and the Chrysler bankruptcy,” recalls Johnson. “Some of those people decided to start their own businesses and slowly Detroit’s economy has become less tied to the big three automakers. That’s a good thing.”

Milwaukee’s “Native Son” Brewers

In the former industrial hub of old Milwaukee in the Menomonee River Valley, Andy Gehl’s Third Space BrewingOpens in new window hides in plain sight under an overpass in a refurbished tin stamping factory that had been part of the humming manufacturing district since the early 1900s.

Gehl and his business partner are part of the boomerang brand of brewers who left their depopulating cities in search of greener pastures only to realize that in the brewing business, there is such a thing as a homecourt advantage.

“The people of Milwaukee want to support a native son and for us, it’s become sort of a selling point,” says Gehl. “Our customers find out we’re originally from Milwaukee and it really matters to them.”

Locating a beer manufacturing business in an area that was always built to be a manufacturing hub has also been a marketing boon.

“You’re seeing people elsewhere trying to recreate what we have here naturally and authentically,” says Gehl. “We’re in an old factory building with that industrial vibe with Cream City bricks and you see people trying to manufacture that by scuffing up their cement floor to make it look like it had forklift track marks on it. That’s fake and people sense that.”

However, Gehl admits that the windfalls that come from locating in a less-than-desirable area have been more incidental than purposeful.

“Before we moved in nobody came around here unless they were coming to drag race, but us moving in wasn’t necessarily some part of a master plan,” recalls Gehl. “It was affordable and met our needs.”

(READ: Breweries with Hotels, Inns, Camping and More)

Reviving Milwaukee’s Industrial Beer Town Legacy

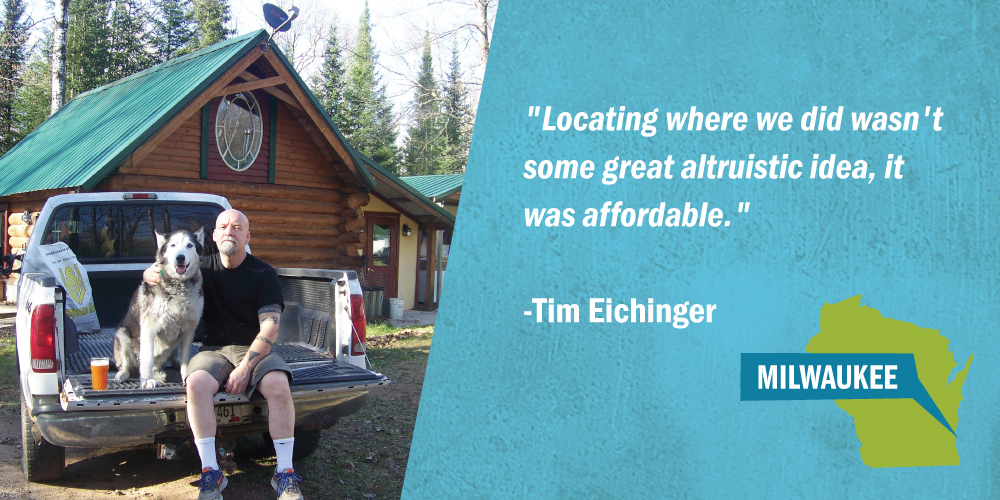

In 1999 Tim Eichinger and his wife, Toni, moved to a Wisconsin village named Pembine. There, they built a log house cabin and planned to raise their son (and his 23 sled dogs) in bucolic bliss.

However, soon they began homebrewing, which led to a business idea that upended their pastoral existence. Within a year they were getting delivery requests from Milwaukee bars and restaurants wanting to serve their beers.

“I was driving once a week in a van delivering beer kegs and cases and at some point, it just made more sense to relocate to Milwaukee,” says Tim.

Tim and Toni found a decaying 1920s automotive repair shop building and bought to house Black Husky BrewingOpens in new window it after realizing their budget would not allow for many other options.

“We wanted something we could buy, not rent,” says Tim. “Also, as a brewer I wanted to make sure I had a high ceiling, big doors, and garage entryway we could open. We wanted to have a small outdoor spot, also, and then a taproom. The building we were buying had all those things.”

It also had a ton of industrial litter strewn all over most of the space.

“For us it was seeing past the broken down cars and boarded up windows and seeing the potential of the space,” says Tim. “Sure, the building was in terrible shape and not in a trendy neighborhood, but it had what we needed: affordability.”

Tim says he is proud to own a brewery in a neighborhood attached to Milwaukee’s beer town legacy.

“Beer built Milwaukee and our neighborhood, River West, is where a lot of the people who actually worked in the breweries lived,” says Tim. “People from the suburbs see this neighborhood now and think that it’s a high crime area, but people in nearby neighborhoods think this is an eclectic, bohemian area with lots of neat things to do. I guess the suburbs probably have their own breweries.”

Coming together for food and drinks is a form of ceremony that humans have observed since time immemorial. From pharaohs to paupers, and Dionysus to Homer Simpson, beer has been celebrated as civilizations rise and fall through history.

Today, brewers are at the forefront of a movement to humbly learn from our country’s mistakes. They are not simply skirting around blight and urban decay, but instead, they are embracing a proud history of resourcefulness. They are, in very literal terms, building solutions on top of rubble.

Although it would be tempting to frame their stories in terms of fatalistic David and Goliath pessimism, most would be quick to point out that in that story, David won.

CraftBeer.com is fully dedicated to small and independent U.S. breweries. We are published by the Brewers Association, the not-for-profit trade group dedicated to promoting and protecting America’s small and independent craft brewers. Stories and opinions shared on CraftBeer.com do not imply endorsement by or positions taken by the Brewers Association or its members.

Share Post