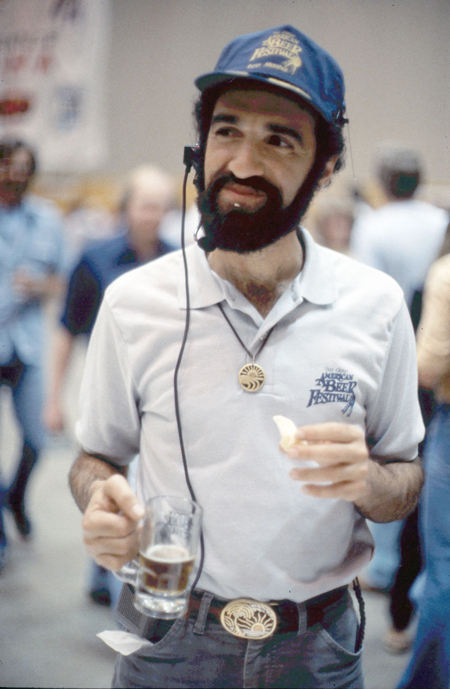

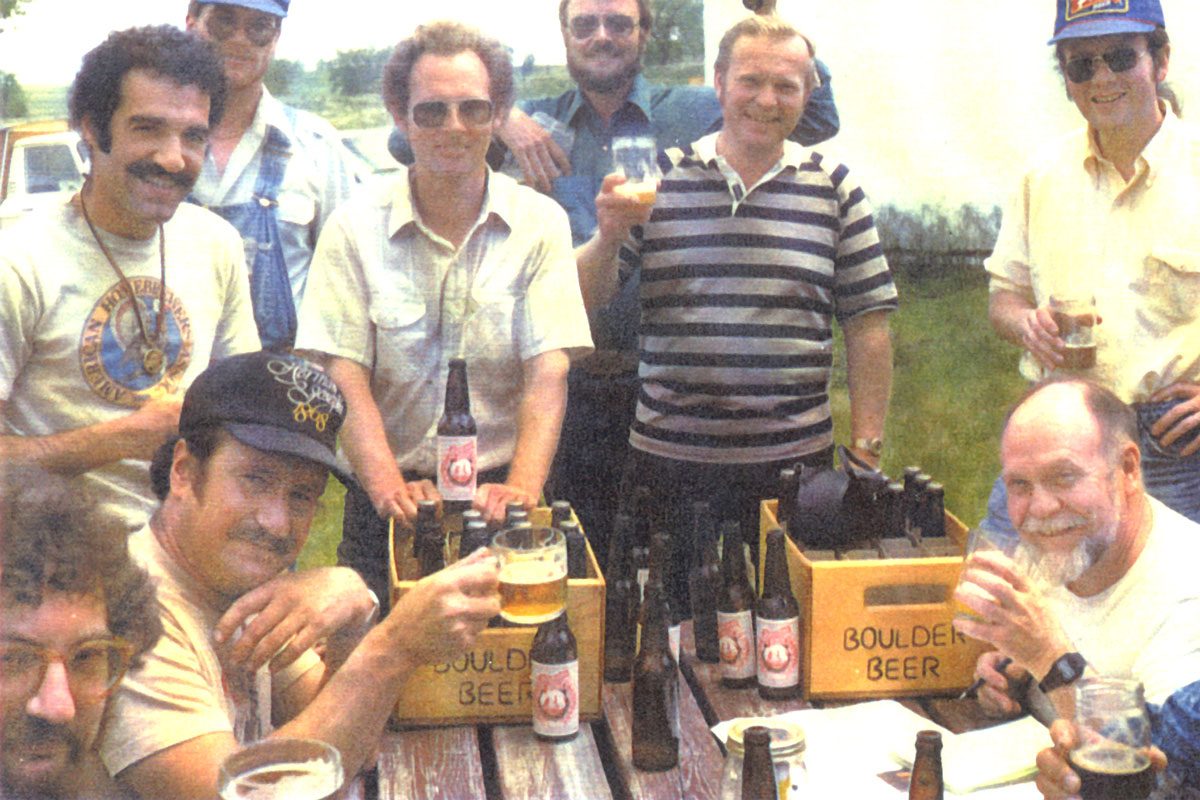

Amelia Earhart flew a plane. Chuck Berry rocked an electric guitar. To secure his place in history, Charlie Papazian — the father of America’s transformational homebrewing and craft brewing cultures — twirled a wooden spoon.

Just this week, Papazian announced he’d be exiting the Brewers Association in January 2019, marking four decades of influence on American brewing. His spoon is part of the story.

For its role in the first dozen years of Papazian’s tasty overthrow of America’s beer culture, Papazian’s wooden spoon — 18 inches long, wort-stained and worn from hundreds of brewing days — has a new address in the nation’s capital. Later this year it will become part of a Smithsonian Institution National Museum of American History exhibit entitled “FOOD: Transforming the American Table 1950-2000.” Centerpieced by Julia Child’s reconstructed home kitchen, the exhibit chronicles the “impact of innovations and new technologies” on America’s post-World War II food and drink landscape.

(READ: Smoke Beers: Historical Beer Style Catches Modern Fire)

The “FOOD” exhibit will feature a new section that for the first time in Smithsonian history showcases the rise of homebrewing and craft beer in America. “It’s well deserved and a little bit overdue,” says Theresa McCulla, the Smithsonian’s recently hired historian for the museum’s American Brewing History Initiative, which was made possible through a donation from the Brewers AssociationOpens in new window, the not-for-profit trade association dedicated to small and independent American brewers, and publishers of CraftBeer.com.

“Beer has become central to American culture. And you can’t tell the history of craft brewing without Charlie,” McCulla says.

Papazian’s wooden companion was a central part of his story.

The Spoon as a Starting Point

“A spoon,” he says, “is the starting point for everything a brewer stirs up. How important is that? The spoon is the hero, mixing and swirling things. Everything starts right there.”

In 1973, Charlie’s spoon was a humble, $1 kitchen utensil setting on a hardware store shelf in Boulder, Colorado. “I was walking down an aisle in the store,” he recalls, “and that spoon spoke to me. It said, ‘Give me a try, I’m special.’ That was the start of our affair.”

What an affair it has been. The spoon was the go-to tool for Papazian as he launched his homebrewing classes in 1973, founded the American Homebrewers AssociationOpens in new window in 1978, and began publishing “Zymurgy” magazine that same year. The spoon whirled wort as Papazian penned the planet’s top-selling homebrewing book, “The Complete Joy of Homebrewing,” released in 1984. It was there when Papazian launched The Great American Beer Festival in 1982 and when he started the craft beer trade group now known as the Brewers Association.

(LEARN: 75+ Beer Styles)

In the early Seventies, the spoon conjured its magic with limited supplies. “There wasn’t much to work with,” says Bill Moore, who founded California-based homebrewing supply company Williams Brewing in 1979. “Lousy dry yeast, bad and usually old malt extract, and semi-fresh hops were all you could find. For hops you had Cluster and Bouillon, and Cascade if you were lucky.”

Malt extract kits called for hefty amounts of added sugar, hops came pressed in brown bricks, and the tools of the hobby were a far cry from today’s sophisticated options.

“Back then,” recalls longtime Celebrator Beer News publisher and editor Tom Dalldorf, “brewing supplies carried warnings: ‘Do Not Add Yeast’. Homebrewing was illegal.”

Papazian bought supplies from a wine-making supply store in Boulder and a retired Navy man who dealt hops, yeast, malt and used acid carboys out of an old and cluttered house. “Going to see the ‘The Colonel’ to buy supplies was always a legendary experience,” Papazian recalls.

That the hobby existed despite its illicit status was a sign of the times. “If you were doing something,” Papazian recalls, “that was fair and maybe a little bit outside of the letter of the law, but that improved people’s lives, it wasn’t a problem.”

(LEARN: CraftBeer.com’s Big List of Beer Schools)

Teaching the Pioneers

Papazian taught his early homebrewing classes out of a string of houses he rented in Boulder. From 1973 to 1982, he taught five semesters per year, five classes per semester, with 20 people per class. The classes covered beer and the then-novel practice of beer judging. Mead making was an occasional topic and classes sometimes included showings of “Homebrew Madness,” a home movie Papazian helped produce with AHA co-founder Charlie Matzen that parodied the anti-marijuana film “Reefer Madness.”

“Students had to get their hand on the spoon,” Papazian says. “They gave it a turn and got the ingredients going in the pot. It was an important part of the class and a lot of people touched that spoon.”

“Beer has become central to American culture. And you can’t tell the history of craft brewing without Charlie.” Theresa McCulla, American Brewing History Initiative

A lot of people were touched by it, too. Jeff Lebesch, a co-founder of New Belgium Brewing with his then wife Kim Jordan, took one of Papazian’s first brewing classes. So did Bill Hasse. “Taking the class,” he says, “was something fun and different, and a reaction to light beer taking over the beer industry. You could make beers that were like the German imports that you couldn’t afford to buy.” Hasse went on to a lengthy beer career that included stints with Boulder micro-breweries and over 20 years with Coors Brewing.

(INFOGRAPHIC: How to Choose the Right Beer Glass)

Those first classes also included Russell Schehrer. A few years later he was crowned as the AHA’s 1984 Homebrewer of the Year, and in 1988 he became the founding brewer for Wynkoop Brewing Company, Colorado’s first brewpub. Today the Brewers Association’s annual innovation award is named for Schehrer. His partner was an out-of-work geologist named John Hickenlooper, who used his brewpub success to launch a political career that made him the mayor of Denver and the current Governor of Colorado.

“I always think of Charlie as a young and enthusiastic Merlin of the beer movement,” the governor says today. “He was a thing to behold.” Would Hickenlooper be in the governor’s mansion without Charlie and his spoon? “The world works in mysterious ways,” he says, “but yes, I think you could say that.”

Papazian’s efforts also shaped the laws of the nation. “Charlie’s ‘Joy of Brewing,'” Dalldorf says of Papazian’s self-published, 78-page predecessor to “The Complete Joy of Homebrewing,” “was fundamental to the hobby of homebrewing and led to the legalization of it in 1978,” via a bill signed by President Jimmy Carter. The book also boosted the hobby’s popularity.

“It was the first book about homebrewing for the mass market,” Moore recalls. “Rather than approaching it as a cult and niche hobby, Charlie really publicized it and gave it a national audience.”

Of course, that homebrewing Bible and wort-stained utensil served as catalysts for a growing congregation of beery disciples that turned their avocation into a vocation. These dreamers launched some of the first craft breweries and continue to swell the small-batch brewing ranks to over 6,000 craft breweries today. That brewery tally was unimaginable when Papazian and his spoon crossed paths in 1973. At the time there was just one micro-brewery in the United States: San Francisco’s Anchor Brewing (which was acquired by Japanese beverage company Sapporo in 2017).

“It makes for a stirring tale, doesn’t it?” Papazian asks. “The spoon,” he adds, “has been a witness to the evolution — and the revolution — of homebrewing and craft beer. When you hold it in your hand now, it kind of vibrates a little bit. It’s got so much mojo in it.”

(VISIT: Find a U.S. Brewery)

Charlie’s Spoon Finds a Place at the Smithsonian

To hold that spoon now requires protective gloves and a Smithsonian security clearance. After a recent going away partyOpens in new window at the Brewers Association headquarters in Boulder (where staffers and friends got a final chance to touch a piece of brewing history), the spoon now resides in Washington D.C. in advance of its upcoming place of honor. It will soon be joined by a 20-gallon trashcan Papazian used for his original “pail ales,” a yellowed homemade copy of “The Joy of Brewing,” and a few other items of Papazian’s.

“The exhibit,” McCulla says, “will tell a founders story of craft beer. It’s a story of changing tastes in America and an amazing entrepreneurial spirit, of people like Charlie Papazian and Ken Grossman making something different that wasn’t available at the time.”

The spoon joins a small but impressive list of Smithsonian peers that includes ancient spoons, presidential versions, and spoons used by the late Julia Child.

“My goal here,” McCulla says, “is to find objects that were central to the careers of influential people. So Charlie’s spoon is really a perfect object for us to collect. It’s not something fancy or ornate. But it’s a great example of how people can change the course of American history by the way they use things. Charlie’s impact reaches so far. His story starts with a simple wooden spoon.”

CraftBeer.com is fully dedicated to small and independent U.S. breweries. We are published by the Brewers Association, the not-for-profit trade group dedicated to promoting and protecting America’s small and independent craft brewers. Stories and opinions shared on CraftBeer.com do not imply endorsement by or positions taken by the Brewers Association or its members.

Share Post